Introduction

Making configuration changes is REALLY easy! …wait, why do you have that look on your face? That mix of ever-so-slight irritation and “WTF is this guy talking about???” I mean, come on, you just punch config t into your Cisco device and then interface GigabitEthernet1/0/1 and shutdown! Who cares if that’s your only uplink to the rest of the network? Not like it matters if it goes down anyway…

…oh, it does matter? Ah! Well, gosh darn it, you should’ve told me that you wanted your configuration changes to, like, actually work! That makes configuration changes a lot harder!

In any event, on a serious note, I’ve been playing around with Nokia SR Linux and Containerlab for a few reasons! Ultimately, the main reason is that they’re both just really cool platforms. Maybeeeee….even Costco hot-dog cool! …okay, no, not that cool, but the fact that it takes some serious thought to come to that conclusion is a serious compliment to the peeps at Nokia!

In case you haven’t seen either of these platforms before, let me give you a very quick 15 second introduction to both:

SR Linux

SR Linux is a modern NOS that’s currently built to run on Nokia’s datacenter hardware. Think along the same lines of Cisco IOS, Juniper Junos, Arista EOS, SONiC, etc. Obviously, all of these are great software platforms for networking, even if one of them makes me look longingly at my local bottle of apple juice sometimes (lookin’ at you, SONiC…love ya!) However, a lot of these platforms have been around the block for decades by this point. As such, they’ve got a considerable amount of tech debt. For example, since the CLIs of many of the aforementioned platforms were built before this automation-native era that we’re living in, the automation functionality was simply bolted on top of the existing platforms. Granted, in most cases, it was done superbly well, since there are some smart cookies working in the engineering departments of all of those organizations! However, since they can’t make any substantial changes to the structure of the CLI without pissing off a metric ton of customers, the result is two separate worlds with different structures: the CLI (defined using the traditional structure) and automation interfaces such as NETCONF (defined using a modern structure/model, like YANG). This often comes with a considerable learning curve to get comfortable with the new structure specifically for automation.

That’s where one of the biggest strengths of SR Linux comes into play. Its CLI is entirely based around a consistent YANG model that is also applied to the structure of its automation interfaces, so our knowledge of one structure translates to multiple ways of interacting with the configuration of our SR Linux devices. Granted, there are many other strengths to SR Linux, but this is a big one!

Also, to be clear, Nokia’s not the only one doing this. We can look to, for example, the OS run by Cisco’s SD-WAN (formerly known as Viptela) routers and controllers. All of the CLI commands are actively being translated to a NETCONF-YANG transaction on the backend, so there’s that synergy between the CLI and automation models. Fun fact: if you ever push a CLI configuration from vManage/SD-WAN Manager to your edge routers that is invalid and generates an error, you’ll see a YANG path showing you where the error in your configuration is, proving that it really is using NETCONF/YANG on the backend!

](/images/nokia-containerlab-digital-twin-cicd-concepts/srlinux-yang.jpg)

Figure 1: Comparison between traditional network OS and SR Linux models, Image Source

However, Nokia’s the one we’re focusing on now, so…yep! In general, SR Linux is just a very clean, open/extensible platform that makes for a very capable NOS!

Containerlab

Containerlab is a VERY cool network emulation platform. There’s what everyone calls “the three mob bosses of network emulation” – GNS3, EVE-NG, and Cisco Modeling Labs (CML). Okay, you got me, no one calls them that. Imagine how cool it would be if they did though! In any event, these three platforms are primarily designed with virtual machines in mind. That makes a lot of sense, since a solid 90% of network appliances and virtual network devices (e.g., routers and switches) run as VMs. From the perspective of building the software images for these devices, running them as VMs provides a clean, isolated environment for the vendors to build in the required functionality to properly emulate their respective hardware/production platforms.

However, because this newfangled thing called Linux (it’s only, like, 30 years old – that’s just downright young!) has gotten really popular lately, many network devices are secretly (or, not so secretly – I’m looking at you, SR LINUX!) running their software as packages/modules on top of a Linux-based operating system. This opens a really cool door to running this software as a container on top of a Linux container host, since the environment no longer needs to be particularly special – it just needs to be Linux, and Linux is everywhere! See my above point about Linux being the popular kid. Doing so allows us to run these virtualized devices much more efficiently, for the same reason that containers consume comparatively less resources than virtual machines in any other application – we only need to worry about including the unique software packages for our network devices in our containerized images, rather than duplicating everything about the environment.

The trouble is that running containers can be a bit challenging, especially for newcomers. Let’s just say that container networking infamously has the potential of being quite obtuse. As such, the primary goal of Containerlab is to let us get the boring container stuff out of the way by abstracting all of those details and allowing us to focus on defining the relevant aspects of our networking labs (e.g., the nodes and links in the lab). Containerlab will figure out how to spin up our containers in a way that satisfies our lab topology! That’s not to say that the traditional three can’t run containers – they can! It’s just that Containerlab (aka clab) is natively designed for it, so there’s a lot of container-specific creature comforts.

As an aside, this also means that I vehemently disagree with some people’s idea to run every type of network node (including VM-based images) in clab using what I find to be quite a clunky workaround in the form of a software package called vrnetlab that, essentially, packages a qcow2 image with a QEMU/KVM hypervisor together inside of a container image to make it work with clab. Will it work? Yes. Will it perform well? Probably – it depends on the exact image. However, it’s about like trying to cut a Phillips-head screwdriver and transform it into a flat-head screwdriver. Sure, there are times where it might be necessary (e.g., for convenience when mixing traditional VM-based network platforms with container-based ones in a single lab), but otherwise, why not just use the tools for what they’re natively built for?

See, 15 seconds, am I right? …no? Well, maybe it’s just a time zone thing – I’m sure it was 15 seconds somewhere else!

What Are We Doing Here?

I’m so glad you asked! I mean, I don’t have a mic in your room, so I don’t know for sure whether you’ve asked – I just figured that, between all of the amazing jokes and 2 minute 15 second explanations, the question must be on your mind by now!

But First, An Awesome Fact About Containerlab!

One awesome detail about Containerlab is that everything that comprises the entire state of the lab (e.g., configurations, the lab topology itself, etc.) is stored as files inside of a series of folders. This is VERY, VERY handy, as it means that Containerlab labs (wow, say that five times fast!) are extremely portable. In other words, I can work on a lab with Containerlab on my local system, and then just hand off the entire folder to you. From there, you can fire up the lab on your system and, as long as you’ve got all of the container images that I used installed in your local container registry, you’ll have the exact same lab that I was working on! Mind you, I don’t just mean the same nodes in the same topology – down to every line of configuration that I saved, the exact same lab!

This is unlike other network emulation platforms, where the state of the VMs that represent the network devices is stored on individual qcow2 images (VHDs) for each node that aren’t easily exportable. As such, on GNS3/CML/EVE-NG, you can just as easily export the lab topology itself as you can on Containerlab, but not the state of the nodes themselves. The reason for this goes back to a fundamental difference between VMs and containers. Because VMs are entirely self-contained/isolated environments, all of their state is stored on their respective virtual storage devices. All three of these network emulation platforms keep those node-specific qcow2 files tucked away in separate directories from the main lab topology definition file. By contrast, recall a fundamental fact of life with containers: containers don’t have any persistence on their own. By default, all a container boots up with is anything that is included in its container image. For containers to have persistent storage, we need to expose a filesystem path on the container host to the container. If our network devices are natively containerized and built with this model in mind, this allows them to directly save their configuration files to a directory on the container host.

Is your brain going “woooaaahhhhh” at this point, like you’re on a roller coaster? Perhaps an example will make this more clear. For SR Linux, the configuration file is stored in the /etc/opt/srlinux/config.json file on the device, no matter whether the device is a real switch or a virtualized container. If we inspect an SR Linux container that I have running for something else using the docker inspect command, we’ll see the relevant section here:

"Mounts": [

{

"Type": "bind",

"Source": "/home/kelvintr/labs/clab-nokia-multi-dc-lab/dc1-leaf5/config",

"Destination": "/etc/opt/srlinux",

"Mode": "rw",

"RW": true,

"Propagation": "rprivate"

},

For context, this pertains to a node called DC1-Leaf5 running in a lab called “Nokia Multi-DC Lab”. Notice that the /etc/opt/srlinux directory inside of the container is mapped to a config folder for the specific device (dc1-leaf5 in this case) that is further contained inside of a lab-specific folder (clab-nokia-multi-dc-lab). Effectively, whenever we save the config.json file in this SR Linux container, that file will actually be saved to /home/kelvintr/labs/clab-nokia-multi-dc-lab/dc1-leaf5/config/config.json on the container host, as shown here:

kelvintr@ktl-clab-svr01:~/labs/clab-nokia-multi-dc-lab/dc1-leaf5/config$ ls config.json

config.json

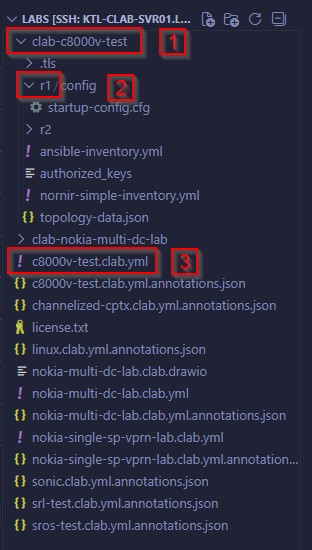

Figure 2: Example folder structure for a lab in Containerlab: (1) Lab-level directory, (2) Device-level directories, (3) Containerlab topology file

Note that this concept doesn’t really work for most VM-based nodes running inside of vrnetlab, since they’re fundamentally still VMs, even if those VMs are running inside of a shell container. As is the case with the other VM-based network emulation platforms, this means that all of the state for our VM-based nodes is saved to a qcow2 file, rather than directly as a file to our filesystem. Fortunately, for most VM-based devices, Containerlab has a hook into the CLI of the devices that allows it to pull out the startup config and save it as a file to the device-specific config directory when we run the

clab savecommand on that lab. That way, even though the container itself has no persistence (even if we save the startup config in the VM, when the VM/container reboots, it will go back to the default configuration), we can load a specific configuration on every reboot and override the default config. Again, yet another reason I think clab with vrnetlab is a bit clunky!

How Is This Useful?

Wow, there’s two of them! Two of the same lab! Wait, digital twin? Well, not quite! On its own, this portability doesn’t really do much for us. Yes, it’s cool that we can easily share labs with our friends, but…what does any of this have to do with automation? Well, stay with me here, because this is about to get SUPER cool, but also super wonky to think about if you’re not used to this mindset.

Think about the ways that we have of sharing files. On the one hand, there’s the good olde sneakernet; just run it over with a USB drive! We could choose that method to share our Containerlab files, but there are better ways that involve less of that disgusting “putting on shoes and touching grass” stuff! For example, we could compress all of the state for our lab into a ZIP file or share all of the files using Google Drive, Dropbox, and the like. That works, but it’s a bit clumsy, especially if we’re going to be making constant changes to our lab. Now, these challenges aren’t new. They’re the exact same challenges that developers face when trying to share the files included in a codebase: how do we share code files that are constantly evolving with many developers working on them at the same time? Imagine if developers uploaded a new copy of the codebase to Dropbox whenever they made a change. That would be a nightmare! Instead, they resort to uploading the code to a version control system, such as Git, using a repository that keeps track of changes and hosts the code for many people to come along and work on it.

The gears might be spinning in your head right about now. “Wait a second…aren’t labs in Containerlab just a bunch of files and folders, just like a codebase is? Can we just create a Git repository for the lab and host all of the files there?” You betcha! We sure can! A Git repository makes it extremely simple to share Containerlab topologies with others, since other people can just clone the repository and have the exact folder structure that they need to boot up that exact lab state without any fuss! However, Git repositories also come with a plethora of other interesting possibilities that other methods of sharing our labs just simply don’t. They allow us to store multiple variations of the state of our lab, for example. Additionally, for our purposes, they’re extremely handy for network automation, in large part because they enable us to create CI/CD pipelines.

What The Heck Is CI/CD?

For the uninitiated, CI/CD stands for continuous integration and continuous deployment/delivery. The exact nuances concerning the differences between continuous deployment and delivery aren’t particularly important to our conversation, so we can effectively treat them as if they’re one and the same, even if they’re technically not. Essentially, CI/CD pipelines are a way for us to automate the process of merging any changes we’ve made into the existing baseline code/configuration, testing our changes to make sure that they work properly and don’t break any existing functionality (this is arguably the most important thing about CI/CD and will be VERY, VERY handy to us throughout this project), and deploying those changes into production if they pass our tests. We call them pipelines because, similar to a pipeline at a manufacturing facility, they consist of distinct stages that our product (i.e., our code/configuration) need to pass through, one after the other. In most cases, if one stage fails (e.g., if one of our tests fails to pass), we’ll want to kill the pipeline right then and there, although there are cases where we may want to deviate from this assumption.

CI/CD was originally designed for application development, in order to reduce the time to market for new versions of applications. Traditionally, massive changes were pushed all at once, but, especially with large projects developed by many people, this resulted in a lot of messy merge conflicts (i.e., situations where multiple people have made different/conflicting changes to a single section of code) that took a lot of time and effort to resolve and made it difficult to jump around different parts of the project and work on multiple things at once. Anyone who has ever had to fix a tangled-up merge conflict will tell you: it would literally be more enjoyable and less emotionally taxing to fight Godzilla. As such, when Agile workflows that demanded flexibility in being able to work on different parts of the codebase at once became more popular, so did the idea of breaking up those big changes into many smaller changes and continuously integrating them back into the main codebase to make sure that everyone was working on a reasonably up-to-date version of the codebase. With so many changes being integrated back into the main codebase super often, however, testing is hard to do reliably when it’s being done manually by a human, hence why automated testing took off! Additionally, since new features were being more quickly developed and merged back into the main codebase, it made sense to create an automated system to deploy these changes into production, so that users would be able to leverage those new features more quickly, rather than having those changes sit and wait until the next scheduled major version release. Consequently, continuous delivery also came into the fray as an increasingly popular solution alongside continuous integration, hence the almost-ubiquitous pairing of CI/CD.

Notice that CI/CD was, as many things are, born out of blood, sweat, and tears. Even though this example relates to developing applications, configuring networks involves a lot of the same challenges! When there’s a lot of engineers working on a big change to the configuration, it’s often difficult to coordinate changes and make sure that there aren’t duplicate and conflicting changes being made across the devices in our network. Furthermore, especially for large networks with many configuration changes, manual testing is…I’ll just be frank, a giant bore! It’s also risky; you’ll never know whether you’ve caught all of the edge cases, or whether you’ve forgotten to test some weird situation on a subset of devices in the network, such as a case where BGP fails, but only if the Moon is 67% of the way lit up or something. By the way – ha, 67! I’m a kid at heart, after all!

This isn’t just a theoretical conversation - many, many failures/outages from some big companies (lookin’ at you, Cloudflare!) have stemmed from insufficient testing before configuration that breaks in weird edge cases gets pushed out. When many networks are becoming more and more mission-critical, the old adage of “eh, lab in prod, if it breaks, it’ll sort itself out!” doesn’t really work anymore.

Beyond that, when we apply continuous integration to our network configuration by breaking our changes up into smaller changes and merging it into our production configuration more often, that creates a lot of work when it comes to actually deploying those changes to our network devices. In an age where many large networks have hundreds of thousands of devices, deploying this volume of changes is a job for automation and continuous delivery!

](/images/nokia-containerlab-digital-twin-cicd-concepts/gitlab-pipeline.jpg)

Figure 3: An example of a CI/CD pipeline in GitLab, Image Source

](/images/nokia-containerlab-digital-twin-cicd-concepts/gitlab-cicd.jpg)

Figure 4: Architecture behind a CI/CD workflow, Image Source

What Are Digital Twins?

There’s one more challenge with networks that we’ve yet to talk about, and it relates back to a classic programming joke. “What do you mean the program bugs out on your computer??? IT WORKED FINE ON MY SYSTEM!!!” Those words – “it works fine on my system” – are so common, they’ve become one of the most overused (yeah, I said it!) programming memes at this point. However, this is also an issue when it comes to developing new configuration and testing changes to our network. Because many networks have become so large, it’s fairly common practice to build a “representative” lab environment that includes what we think is the relevant subset of devices and configuration that we need to build out our configuration changes and test them. That way, we don’t need to include hundreds of thousands of devices and millions of lines of config if our configuration changes are only going on two of the devices and only affects the OSPF section of our configuration. However, this always opens up the possibility that something we haven’t included in our lab environment is impacted by our configuration, or vice versa.

That’s where digital twins come into play. As you might’ve already gathered from the word “twin”, digital twins are meant to be lab environments that serve as identical replicas of our network. Ideally, they’ll contain all of the devices in our network and all of their configurations. Sure, we may not be able to capture literally every detail, like the exact hardware platforms at play, since that would be insanely cost-prohibitive! Imagine justifying the purchase of a couple million dollars of physical equipment just to emulate the network in a lab; that’s an awkward conversation, especially when virtualized network devices exist that allow us to accomplish a similar goal by digitally emulating most of the real functionality of the actual network at a fraction of the resource/financial cost. Along these lines, digital twins give us an unmatched ability to easily figure out what configuration we actually need to push to achieve the goals behind our change, visualize the precise impact of our changes, and run extensive tests before those changes ever touch production.

Tying everything back together, with a sweet little ribbon in whatever your favorite color is, imagine the power of digital twins and CI/CD together! Digital twins make it much easier for everyone to actually figure out and build the configuration changes that we need, and continuous integration gives us the tools and techniques that we need to break those configuration changes up into smaller ones and continually merge them back into our main configuration! On top of that, digital twins also give continuous integration the power to run whatever tests it needs to, prior to integrating our configuration changes, by leveraging scripts. The best part? All of this is entirely separated from our production environment, with zero risk of downtime if ANYTHING goes wrong. Beautiful!

Our Plans For This Project

Ultimately, all of this encapsulates the spirit of NetDevOps: applying the same techniques that we figured out while solving the challenges with application development to solving the challenges of managing deeply entangled, sprawling, global networks. So, what are we waiting for? Let’s actually put all of these NetDevOps concepts to use with a project that allows us to spread our wings and practice them! Broadly speaking, we’ll be building out a small-scale example of a production network using Nokia SR Linux (it could be another platform, but I like SR Linux and the native automation capabilities of SRL is going to make this a breeze!), building its digital twin and integrating it with Git, developing our suite of tests, and configuring the automatic integration/deployment of the changes that we modeled in our digital twin to our actual production network!

Well, this blog post has already gotten pretty long, so let’s split this up into three parts:

- This post - introducing us to the concepts

- The next post - setting up our lab environment with the tools that we need to make all of this work

- The post after that - actually building out the CI/CD pipeline and seeing it all come to life!

Excited? Yep, so am I! Let’s get to it in the next post. I’ll make sure to include a link all of the other blog posts here when they’re ready, so that you can easily navigate to them.